An unprecedentedly low level of interest rates in the advanced economies has triggered a massive surge in capital flows to emerging markets. In order to stem further currency appreciation, Brazil has stepped up FX intervention and introduced a tax on capital inflows. Should capital inflows persist and the exchange rate remain under pressure, the central bank may well opt for greater FX intervention, not least in order to pre-empt potential threats to its autonomy. Should the central bank resist greater intervention, the government may feel compelled to choose between curtailing the autonomy of the central bank and tightening capital controls.

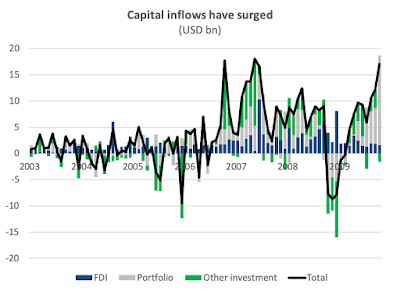

Nouriel Roubini has called it the “mother of all carry trades”. Unprecedentedly low levels of interest rates in the advanced economies and returning risk appetite have triggered a surge in capital flows to emerging markets (EM). Financially weak EMs will welcome the reflow of capital, but EMs with solid external fundamentals will feel more ambiguous about it. While the renewed inflows help ease financing conditions, especially for the private sector, the sheer size of the inflows and the resulting upward pressure on the exchange rate have raised concern about a loss of competitiveness and slower economic growth. EMs with (relatively) freely floating exchange rate regimes, open capital accounts and solid macro-fundamentals have experienced sharp currency appreciations (e.g. Brazil, South Africa).

Brazil provides an interesting case study in terms of the policy challenges this “sudden surge” in capital inflows poses to policymakers. In the face of large capital inflows and considerable currency appreciation, the central bank resumed FX purchases in May and increased intervention considerably in October. In addition, the finance ministry slapped a tax on portfolio inflows in October. These measures seem to have contributed to a stabilization of the real in the 1.7-1.8 range vis-a-vis the dollar.

|

| Source: Banco Central do Brasil |

But what will the authorities do if capital inflows increase further? If the currency is allowed to appreciate, the current account deficit will widen. While this would not be a problem given solid fundamentals (esp. limited foreign-currency mismatches, financing of the deficit through equity rather than debt flows), a rapidly rising stock of foreign portfolio investment would gradually raise Brazil’s vulnerability to yet another “sudden stop” – a prospect no government fancies less than 12 months before a major election. The government’s decision to “lean against the wind” (or storm, if you will) is therefore not surprising.

Brazil was heavily criticised for introducing a capital inflows tax. But what was the alternative? The textbook response would be to tighten fiscal policy in order to put downward pressure on domestic interest rates. However, politically, fiscal tightening is difficult to achieve given next October’s presidential elections. More importantly, economically, it is doubtful that fiscal tightening will solve the problem, for Brazil is experiencing an equity rather than a debt carry trade. In other words, it is Brazil’s relatively strong growth outlook rather than a large interest rate differential that is the dominant driver of capital inflows and currency appreciation.

Another policy option would be to step up FX purchases. Judging by the October data, the central bank already seems to have moved into this direction. If the current surge in inflows turns out to be temporary and reversible, increased sterilized FX intervention looks both financially feasible and politically attractive. This might require the government to order the central bank to step up purchases, should the latter be reluctant to increase the pace of intervention. Alternatively, the government could try to change legislation in order to allow the treasury to make larger FX purchases. However, if capital inflows turn out to be more persistent and permanent, this strategy will be less viable given rising sterilisation costs and the impact increased domestic bond issuance may have on interest rates.

Finally, the authorities could further tighten controls on inflows. Empirical research suggests that controls on inflows tend to be detrimental to medium-term growth and often fail to be very effective, especially in countries with a sophisticated financial sector. But controls do not have to be “very” effective to have an effect and, indeed, to make them politically attractive. Should the central bank balk at stepping up FX intervention, a tightening of controls cannot be ruled out. Currently, the government is studying measures aimed at liberalising capital outflows. But it is far from obvious that such measures will be effective in significantly reducing net capital inflows and currency appreciation, especially in the short term.

One of the prospective presidential candidates is known to have “unorthodox” ideas about how to manage the exchange rate, favouring a weaker exchange rate and lower interest rates with a view to generating “export-led growth”. The stronger the exchange rate in the run-up to and following the presidential elections, the more likely such ideas will gain currency. There is good reason to be skeptical about the likely success of such a “mercantilist” strategy, for as long as domestic investment remains low, a weaker exchange rate and lower interest rates will simply raise inflation and push up the real exchange rate; and in order to generate higher investment, the domestic savings ratio would presumably have to increase. But this is a separate debate.

The political and economic bottom line remains the following. Should capital inflows persist and the exchange rate remain under pressure, the central bank may well opt for greater FX intervention, not least in order to pre-empt threats to its autonomy. Should the central bank resist greater intervention, the current and future government may face a tough choice: curtail the autonomy of the central bank or resort to further “unorthodox measures” (read: capital controls). The government must no doubt be hoping not to have to make this choice. The reality is, of course, it doesn’t have to: it could simply let the exchange rate overshoot given solid fundamentals and manageable foreign-currency mismatches. However, even the IMF expresses some sympathy for (temporary) capital controls. Therefore, if capital inflows remain strong over the next few quarters, the government may find it difficult to resist a further tightening of capital controls.