If the debt ceiling is not raised or suspended by July, the risk of a U.S. government default will increase significantly. Raising or suspending the debt ceiling requires both the House and the Senate to pass a bill to this effect. The Senate is controlled by Democrats, and Senate Republicans are not likely to filibuster debt ceiling legislation (they allowed the adjustment to happen in 2021, and will do so again, as Republican senators are on average more moderate than their party colleagues in the House.) However, House Republicans are strongly committed to extracting budgetary concessions from the White House in exchange for raising the debt ceiling. On April 19, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy published his long-awaited plan laying out the conditions for Republican support for a debt ceiling adjustment. Among other things, the plan foresees capping spending at 2022 levels, rescinding unspent pandemic relief funds, and rolling back energy and tax credits contained in the Inflation Reduction Act, in exchange for a one-year (effectively, until March 2023) debt limit increase of $1.5 trillion. The Democrats, who hold a majority in the Senate, are never going to pass the Republican House bill in its current form, and it is unclear at this point if McCarthy can find the votes to pass the bill in the House. Instead, the proposal is meant to provide the basis for negotiations with the White House over budget policy and the debt ceiling. Meanwhile, the Biden administration insists on a “clean” debt ceiling adjustment (an adjustment without conditions) as a precondition for engaging in negotiations with House Republicans. This would significantly reduce Republican leverage and is therefore a non-starter. The White House and the House Republicans are engaging in a classic game of chicken.

What makes the politics of the debt ceiling more challenging than in the past is that the House leadership, which typically is in firm control of the legislative process, is weak, making it more uncertain that it will be able to approve a debt ceiling increase over the opposition of Republican congressmen, even if it wanted to. McCarthy was forced to make extensive concessions to Republican rank-and-file members, and especially the right-leaning Freedom caucus, to be elected speaker. These concessions weaken his control and make it relatively easy for Republican House members to propose and amend bills as well as making it easier to unseat or threaten to unseat the speaker, thus constraining his actions and room for maneuver. McCarthy was also forced to appoint two right-wingers to the powerful House Rules committee, which gives the Freedom Caucus and less moderate Republican House members greater sway over how a bill is steered through the legislative process, making it much more difficult for the leadership to ensure a speedy process and approval of any bill. Moreover, a very slim majority means that the Republican leadership cannot afford to lose more than four Republican votes if it wants to pass legislation over the opposition of Democrats. This further increases the leverage of Republican rank-and-file members at the expense of the House leadership. A bill that raises the debt ceiling would find the support of minority House Democrats. But a combination of weak leadership and difficult-to-control rank-and-file make the process of proposing, amending and voting on a bill more cumbersome and time-consuming and its outcome less certain. Members of the right-leaning Freedom caucus are especially well-positioned to torpedo any attempts to move any quickly and successfully through the legislative process.

Concerned about the ability of the Republican leadership to pass debt-ceiling-related legislation against the will of its right-wing members, centrist Republicans and Democrats have begun to explore the possibility of supporting a so-called discharge petition. This would allow them to force legislation out of committee and onto the floor for a vote without support from the speaker or the consent of the relevant committee. A petition requires the support of 218 House members (out of 435 votes). Currently Republicans hold 222 and Democrats 213 seats. So if the Senate passes a bill to raise the debt ceiling and sends it to the House, only five Republicans would need to vote with Democrats to force a floor vote. The problem is that a discharge petition is a procedurally onerous and time-consuming instrument. It would therefore need to be approved soon in order for it to be operative by the time the Treasury exhausts extraordinary measures during the third quarter (see below). To pass legislation using a discharge petition would take around 2-3 months. In view of the likely July/ August X-date (the date when the Treasury will exhaust extraordinary measures and will be unable to meet all its obligations), the petition would need to be voted on in the next few weeks for it to help prevent a default.

The degree to which economic and financial dislocation will intensify as the X-date approaches will depend on how long markets expect any default to last and how forcefully the Federal Reserve intervenes to limit the financial fallout. If markets believe that the default is temporary, short-term bills will sell off, but longer-term bonds may rally. Increased economic and financial uncertainty would nevertheless lead to a sell-off of credit and equities. It is therefore possible, but far from certain, that financial instability will remain manageable as long as markets expect the default to be remedied imminently. If, on the other hand, markets believe that Congress is nowhere near an agreement as the X-date approaches or after a technical default has occurred, then the financial and economic consequences could be very dire. Last but not least, the greater the economic and financial distress that a technical default triggers, the more likely Congress will agree to take remedial action.

The Federal Reserve is not likely to intervene too forcefully until a default is imminent or has already occurred. In the event of a default, the Federal Reserve may decide to intervene to limit financial instability. The most obvious option is to purchase defaulted government debt and replace it with debt the U.S. government has not yet defaulted on. Federal Reserve decision-making will be a function of its mandate to maintain financial and economic stability, on the one hand, and the need to avoid providing direct financing to the government for fear of breaking the law and being accused of meddling in politics, on the other hand. On balance, the Federal Reserve will be reluctant to intervene in a manner that risks exceeding its legal mandate so as not to provoke a political backlash. However, should financial instability get out of hand, it would likely find a legal loophole that would allow it to take more forceful action, such as buying/ lending against defaulted debt etc. Hence, the greater the ensuing financial instability, the more likely the Federal Reserve will intervene. But again, it will be difficult for the Federal Reserve to intervene very forcefully until financial instability has increased sharply, or the government has fallen into technical default.

The base case remains an agreement between House Republicans and the White House, which will include some spending reform in exchange for a one-year extension of the debt ceiling, which would likely result in the issue reemerging right before the 2024 presidential election. We believe this scenario has a > 50% probability of materializing. Still, other less likely scenarios are possible:

1. The US raises or suspends the debt ceiling in such a way that the issue will not reemerge until after the 2024 presidential election (30%)

- McCarthy’s current proposal foresees a debt ceiling increase of $1.5 trillion, which would buy the Treasury about a year. (The CBO projects a deficit of $1.4 trillion for FY 2023.) If an agreement between House Republicans and the White House is reached under the current Republican plan, the issue would likely resurface just before the November 2024 elections, assuming that the Treasury would exhaust extraordinary measures within about six months.

- It is possible that both sides agree to a greater increase of the debt, past the 2024 elections. But such a proposal is currently not on the table and the White House would likely need to make significant concessions for the House to agree to a longer extension. The issue seems to play well with the Republican base and particularly with Republican House members in “safe” red seats, as it provides them with a tool to put political pressure on the administration in an election year

- If, however, the centrists manage to pass a discharge petition, it is likely that they would opt for a longer extension until after the 2024 elections, as they would not want to deal with this issue in an election year. This is particularly true for centrist (moderate) Republicans at risk of facing right-wing challengers in the primaries.

2. The US raises or suspends the debt ceiling in such a way that the issue reemerges before the end of 2023 (15%).

- This is not very likely, as Congress would have to pass contentious legislation twice. However, if the X-date were to arrive unexpectedly early in the midst of negotiations (which, admittedly, have not started yet) due to weaker-than-expected tax receipts (see below), both White House and House Republicans would have an incentive to support a short-term extension. Playing hardball that leads to a default in such a situation would be politically costly and undesirable, given that a deal is preferably to a default.

3. The US fails to raise the debt ceiling and falls into a technical default (2%)

- Once extraordinary measures have been exhausted, a technical default will not automatically follow, provided the Treasury succeeds in prioritizing debt over other payments. If the Treasury were forced to take such desperate measures, the market reaction would be negative and increase the pressure to adjust the ceiling. The probability of a default is low, but it is not zero. Markets are of the same view: one-year credit default swap spreads have risen from 20 basis points in January to more than 100 basis points today. This is higher than in 2011 when an agreement was reached at the very last minute.

- In principle, a technical default can be remedied quickly. But a technical default could have unanticipated second-round effects. For example, defaulted securities may not be accepted as collateral, which in turn leads to financial problems for repo transactions etc.. Economically, it may not make much sense to sell government debt securities at a huge discount as long as a default is expected to be remedied quickly. As suggested, much will depend on how markets assess the political outlook for reaching an agreement on lifting the debt ceiling. A possible but less likely scenario would be a dramatic financial market meltdown and a wide-spread destabilization. This is less likely because any technical default is likely to be remedied quickly, or because it would force the Federal Reserve to intervene very forcefully.

The so-called X-date will likely materialize in late July or early August. In January, the Treasury estimated that it was not likely to exhaust extraordinary measures “before June”, even though it admitted that “considerable uncertainty” attached to its forecast. How soon the Treasury will run out of cash to stay current on all its obligations will depend on the amount of taxes. it will receive in the next few weeks, following the mid-April tax deadline. Tax receipts are difficult to forecast with any degree of confidence. If tax revenues remain strong and the Treasury makes it past the next mid-June tax deadline, when it is expected to see increased inflows, it is likely to have enough cash at hand to meet all its obligations until mid-July. The probability that due to weak tax revenues the X-date will arrive in June is low but not non-negligible (10%). The probability that the X-date will fall somewhere between mid-July and mid-September is high (70%). If the Treasury makes it to mid-September, the X-date would likely be pushed back further into late September or October given fresh cash inflows. Markets hold a similar view: T-bills maturing in late July and early August have higher yields and have become more difficult to trade, suggesting that markets see late July/ early August as the most likely time for a default.

The Treasury is unlikely to resort to unorthodox policies to avoid a default, because these moves would be legally risky and their economic-financial outcome would be uncertain. They would be challenged in court and would therefore fail to reassure markets sufficiently and unambiguously. The Treasury is likely to opt for payment prioritization, provided it is administratively and technologically feasible. One might argue that the greater the financial turmoil leading up to the X-date, the more likely the authorities will resort to gimmicky solutions. But they do not offer a bullet-proof solution, which will make the authorities reluctant to opt for them. They would be challenged in court and would therefore fail to reassure markets sufficiently and unambiguously. Equally importantly, extraordinary and legally questionable measures would reduce the pressure on Congress to fund such solutions, which is not desirable from the point of view of finding a sustainable solution. While unlikely to materialize, the list of unorthodox options includes:

One-trillion dollar coin: The Treasury could decide to have a high-denomination coin minted that is then deposited at the Federal Reserve. But this would be legally risky. The Federal Reserve might refuse to accept the coin, which would then force the Treasury to ask for an injunction. Other actors might also challenge the legality of such a decision. (Both Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen and Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell have dismissed the coin option, if not necessarily its legality.) While it is far from clear that it would prevent a crisis given the concomitant legal uncertainties, from the Treasury’s point of view it would be preferable to a disorderly default. But institutionally, it would do great damage to the Treasury and the Federal Reserve, and the United States. Financially, the measure may fail to calm markets, given legal uncertainties. Economically, the credibility of the Federal Reserve would be shot due what effectively amounts to massive monetary financing of fiscal deficits, which might even exacerbate financial market instability. Politically, Congress would likely view such action as arrogating its prerogatives and as meddling in politics and contest such a move politically and legally.

Invoking 14th amendment debt clause: The 14thamendment, and specifically the so-called public debt clause, says that the U.S. government debt shall not be “questioned”. Some legal scholars argue that the constitutional amendment renders the debt ceiling unconstitutional and that the government could therefore simply ignore it by invoking the 14th amendment. Other legal scholars disagree strongly. (The Obama and Clinton administrations held diverging views on this issue.) Invoking the 14th amendment would be fraught with similar legal, economic and political uncertainties as issuing a platinum coin. In addition, it might throw the United States into a constitutional crisis, which would do little to calm financial markets. The Biden administration is very unlikely to invoke the 14th amendment and will instead bet that increasing financial instability will lead to a political compromise.

Instead of opting for such desperate measures, the Treasury is likely to opt for payment prioritization, provided it is administratively and technologically feasible. Although prioritizing payments on financial obligations offers only temporary reprieve, the Treasury is substantially more likely to choose this option to avoid an imminent financial default, provided it is practically feasible. (Both former Treasury Secretary Lew and current Treasury Secretary Yellen have expressed doubt that it is.) While such a decision may also be challenged in the courts, it would nevertheless buy time while not causing the same degree of institutional, reputational and political damage as the other options. Economically, prioritizing financial obligations would nevertheless reduce spending, weigh on economic growth and signal to investors that a default may be becoming increasingly likely. But by buying time for Washington to find a political solution, it will be less destabilizing financially than an outright payment default, which is why the Treasury is far more likely to opt for it than all the other “gimmicks”.

Resiliency of the US dollar as global reserve currency

The dollar is very resilient, if only because there is no viable alternative to it. A global reserve currency refers to the currency denomination of a central bank’s reserve assets, while an international currency refers to the use of a currency in international trade and finance and, more broadly, its private and public use as a store of value, means of exchange and unit of account. While a global reserve currency is generally also an international currency, this distinction is relevant, as central banks may reduce their dollar holdings, while this may leave unaffected the role of the dollar as an international currency. Even today, the share of the dollar in foreign-exchange markets far exceeds its importance as reserve currency.

The short-term impact of a technical default on the international role of the dollar would be limited, provided it does not lead to complete financial and political meltdown, which is quite unlikely. A long-lasting default would lead central banks to sell US government debt without necessarily moving out of the dollar. But with few willing buyers, they would only be able to sell so many debt securities. A short-term technical default would also lead central banks to rebalance their portfolios away from U.S. government bonds and especially short-term bills, if much less so from the dollar. This is so because international trade and financial transactions will continue to be conducted in dollars limiting the extent to which central banks will want to divest dollar-denominated assets. They may somewhat reduce the share of US government securities in their portfolio and move into dollar proceeds to US or international banks.

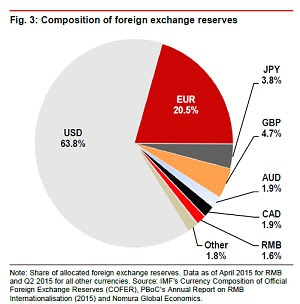

In practical terms, it is also virtually impossible for the major central banks to buy alternative safe assets at a reasonable price, which is why the dollar share in global reserves would decline only very modestly in case of a technical default. The limited amount of global safe assets would limit dollar divestment. Global FX reserves amount to $12 trillion, of which $6.5 trillion are denominated in dollars, a large share of which is held in the form of U.S. government bills, notes and bonds. Dollar-denominated holdings amount to 60% and euro-denominated holdings to 20%, RMB holdings to less than 3%, which makes it virtually impossible for the dollar not to remain the dominant reserve currency. The amount of “safe assets” denominated in other reserve currencies is limited. Moreover, the euro and euro-denominated assets suffer from structural flaws due to an incomplete monetary and fiscal union, and the renminbi is not fully convertible. As a result, at least in the short- to medium-term, the dollar would remain the dominant international currency, even if central bank reserve managers decide to reduce their holdings of US government debt or even their dollar-denominated assets at the margin. Until a credible and practical alternative to the dollar emerges, the dollar will remain the dominant international reserve currency and the dominant international currency.