The rise of the RMB as a reserve currency has garnered a lot attention lately. The Chinese authorities have taken numerous measures aimed at internationalising the RMB and making it “freely usable”, the latter being a pre-condition for a currency to be included in the IMF’s SDR basket (e.g. opening domestic bond and FX market to foreign central banks; making, or attempting to make, the exchange rate more flexible).

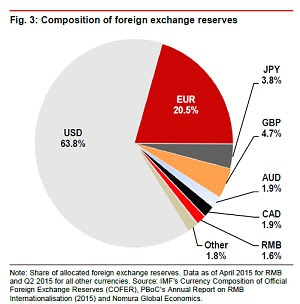

At present, a little more than 1% of global FX reserves are invested in the form of RMB-denominated assets. Some analysts predict that as much as USD 1 tr of global FX reserves could shift into RMB once it is included in the SDR basket. This estimate is presumably based on the likely weight of the RMB in the SDR basket. The share of RMB assets in global (ex-China) FX reserve holdings would then rise to more than 10%. This may well be the share of reserves central banks will want to hold in RMB, but is there a sufficient supply of RMB assets?

Foreign central banks invest in safe and liquid assets. In practice, this means that the bulk of FX reserves is invested in high-grade, central government debt issued by advanced economies. Central banks are far less keen to invest sizeable amounts in higher-risk and/ or less liquid assets. Not surprisingly, almost 2/3 of global FX reserves are denominated in USD and another 20% in EUR. Foreign official institutions held about USD 4.8 tr worth of US debt securities as of the middle of 2014, of which USD 3.8 tr were US treasuries. 80% of foreign official holdings of US debt securities are concentrated in US treasuries. As the foreign official sector includes sovereign wealth funds, central banks are likely even more heavily invested in treasuries.

Credit risk matters, as the decline of foreign official holdings of US agency debt illustrates. Today foreign official institutions hold a mere USD 400 m of agency debt, compared to almost USD 1 tr in 2008. The financial distress Fannie and Freddie experienced during the global financial crisis seems to have scared foreign central bank away. Size necessarily matters. Outstanding US treasuries amount to USD 13 tr and marketable treasuries to almost USD 11 tr. Japan comes relatively close second with USD 8.2 worth of government debt securities outstanding. Only six other countries have central government debt exceeding USD 1 tr (UK, Italy, France, Germany, Spain and China). If one looks at the size of the total bond market, the difference is even starker. With global FX reserves amounting to USD 11.5 tr, the bulk of these reserves will necessarily need to be invested in the US treasury market given its superior size and liquidity as well as, generally, creditworthiness.

Leaving aside liquidity, which is an issue in the Chinese government debt market, there may not be enough RMB assets out there for central banks to invest in if USD 1 tr is to be shifted into RMB. Assuming that 90% of RMB-denominated reserve holdings are invested in central government debt, foreign central banks would end up holding 50-60% of the USD 1.7 tr market. While foreign holdings in the US and Germany are roughly at similar levels, it is far from obvious that Chinese policy-makers or foreign central banks for that matter would feel comfortable with this given the potential implications for domestic interest rates and the exchange rate as well as asset prices and liquidity. This is especially salient in a context where the investor base would largely consist of domestic commercial banks, on the one hand, and foreign central banks, on the other.

No doubt, structural factors support the emergence of the RMB as a reserve currency. In the short term, however, a dearth of RMB assets will make a very substantial shift of FX reserves into RMB difficult. China’s bond markets have been growing vigorously over the past decade. And even though economic growth is slowing, there certainly is room for the central government to issue more debt. It will therefore take time before 10% of global FX reserves are invested in Chinese assets.

Equally important, if the demand for high-grade assets outpaces the ability of the dominant reserve currency country to provide them without jeopardising its financial strength, the system may well be inherently unstable (so-called Triffin dilemma). According to the CBO, US government debt will remain stable as a share of GDP until the end of the decade and then increase under the so-called “current baseline scenario”. (This scenario assumes no policy changes.) True, the US net international investment position has deteriorated sharply in the past few years. Ironically, this has been due to a strengthening economic outlook and rising US asset prices, including the USD. Net fiscal and external requirement will ensure debt sustainability and maintaining confidence in the USD as a reliable reserve currency over the short- to medium-term, but perhaps not the long term. Meanwhile, the demand for safe, liquid assets denominated in a convertible currency is set to outpace the US ability or willingness to provide such assets. Central banks will have an incentive to move into riskier USD assets or move into non-USD assets, including RMB assets. (The slew of sovereign credit downgrades in the eurozone and a declining of German government debt securities will not offer much of an alternative, either.)

In short, the RMB is set to become a more important reserve currency, as China’s sheer economic size and importance in world trade continues to grow, as the demand for reserve assets increases and as China increased the supply of high-grade RMB assets. Like Japan and Korea before, China will gradually remove capital controls and put in place stable, liquid financial markets. This will also facilitate the RMB’s rise. It would be very surprising, however, to see the RMB share in global FX reserves reach even 10% in the near-term given the limited size and liquidity of high-grade RMB assets.