Latin America seems to be experiencing increasing political and economic instability. Governments in Bolivia, Chile and Ecuador have been rocked by protests. The Bolivian president has just been chased out of the country. In Argentina, economic populists defeated the economically relatively orthodox government of President Macri at the ballot box. The release of former President Lula in Brazil may lead to increasing polarization by paving another presidential run in 2022. Venezuela is in the midst of a major humanitarian crisis. Venezuela is also in default on its external debt and the new government in Argentina will have little choice but to restructure or at least reschedule its external liabilities. In Mexico, the second-largest regional economy after Brazil, AMLO, the country's left-wing president, is pursuing a less market-friendly policy than his predecessor. Last but not least, many of the smaller Central American and Caribbean economies have also been struggling with low economic growth and rising debt as well as occasional civil unrest (Nicaragua). Some countries even managed to default on their debt more than once in the past decade (Belize, Jamaica). The economic outlook for the region ranges from disappointing to dismal. This is all the more remarkable given the relatively favourable global economic backdrop.

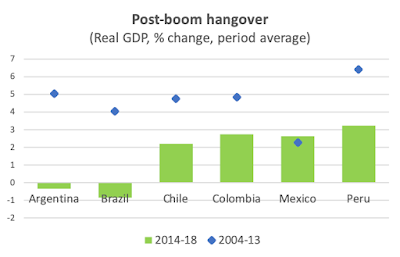

Economic growth has been disappointing. If the IMF’s forecasts are to be believed, five-year average real GDP growth in the region reached a mere 1.0% last year. It is set to fall to 0.6% this year. This compares poorly even to the performance of an advanced economies whose growth rate averaged 2.1%. Five-year average real GDP growth in both Argentina and Brazil has actually been negative, while in Chile, Colombia and Mexico it amounted to 2.0-2.5%. Only Peru will manage to eke out economic growth of slightly more than 3%, down from an average of 7% at the beginning of the decade. Last but not least, Venezuela’s economy is collapsing.

|

| Source: IMF |

Not only is Latin America doing poorly compared to the rest of the world. The region is also faring poorly compared to its past economic performance. Throughout much of the past decade, Latin America was riding high on the back of a commodity boom and, generally speaking, improved macroeconomic policies. Today it is difficult to see what could help lift the region out economic stagnation. Add to this the Eichengreenian middle-income trap and worsening demographics and the region’s growth rate will remain stuck around 2-3% over the medium term - at best. Downside risks abound. For a start, there is a risk then that low growth will lead to a further increase in political instability, less or no economic reform and continued economic stagnation. It is not difficult to see how this could quickly turn into a vicious political-economic cycle.

|

| Source: IMF |

The global macro backdrop is unlikely to improve. The US and European economies have slowed down. The US-China trade conflict continues to weigh on global trade and investor confidence. Advanced economies’ manufacturing sectors are in the doldrums and their fiscal and monetary policy space, though it varies somewhat, is generally limited. Advanced economies’ interest rates are already very low and it is unlikely that further Fed rate cuts would lead to a significant increase of capital flows to Latin America given worsening global sentiment and increasing risk aversion. Furthermore, China’s structural shift away from investment-intensive to greater consumption-led economic growth means that another commodity super-cycle is unlikely to come to Latin America’s rescue. In short, global economic growth has likely peaked. Even if a broader downturn can be avoided, it is difficult to see any upside as far as Latin America growth is concerned.

The outlook for growth-enhancing economic is far from encouraging. In countries like Argentina and Mexico, left-wing and populist presidents are unlikely to pursue major structural reform. Rising public discontent and increased political polarisation will make it harder to implement many of the reforms necessary to reinvigorate economic growth in absence of favorable global economic conditions. True, Brazil just passed an important pension reform. While undoubtedly welcome, it is worth remembering that the reform will only help avoid medium-term public-sector insolvency. Little has so far been done to reduce the infamous custo Brasil and address Brazil’s low productivity and dilapidated infrastructure. Moreover, the release from prison of former President Lula risks increasing political polarizationm, while the prospect of the left returning to power after the next presidential elections in 2022 will do little to lift the economy’s ‘animal spirits’. This will likely be true even if Bolosnaro surprises and manages to push through further structural reform through congress. Venezuela may prove a bright spot, but only if the Maduro government is replaced and a new Venezuelan government quickly resolves its external debt problems. Even then, necessary economic adjustment may prove more contentious, and the political transition more acrimonious, than many markets analysts anticipate. In short, the outlook for growth-enhancing structural economic reform in the region’s three largest economies, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico, which account for 2/3 of regional, is somewhere between modest (Brazil) and poor (Argentina, Mexico). The fact that economic fundamentals remain relatively sound in Chile, Colombia and Peru in spite of elevated but generally manageable political risks does not alter the fact the outlook for Latin America as a whole will remain poor.

Many Latin American countries arguably continue to be plagued by their colonial past, paternalistic-corporatist state structures and an over-reliance on commodity exports (North, Summerhill & Weingast 1999; Rodrik, Subramanian & Trebbi 2002). Government-owned companies continue to play an important economic role and often offer opportunities for corruption and mismanagement. The rent-seeking of various politically influential economic and societal groups causes economic inefficiencies. The continued dependence on commodity exports renders Latin American economies vulnerable to repeated terms-of-trade shocks. The legacy of an inward-looking development strategy has not been completely overcome and many economies have failed to integrate themselves into global supply chains - Mexico and several Central American economies excepted. While some countries have made some progress with respect to several of these challenges (Chile, Colombia, Peru), others have been less successful (Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela). It is therefore not very surprising that Argentina is due for another external debt restructuring and Venezuela is in default. Neither Brazil nor Mexico is at risk of a near-term external payments default. However, their sovereign credit profile has weakened in the past few years due to rising public debt. Once one realises that the deterioration in economic fundamentals has taken place against the backdrop of solid global economic growth and record-low global interest rates, it is worth asking two questions. What will happen to the region’s economic outlook, should advanced economies experience a further slowdown or even a recession? How will a further deterioration of regional economic conditions affect political stability, more broadly, including the ability of the various governments to pursue stability-oriented economic policies?