The increasing weaponization of economic interdependence creates major risks for economically open countries. American-Chinese geostrategic competition is forcing all the major powers to reassess and address their respective vulnerabilities as well as increase their geo-economic leverage. ‘Qualitative’ decoupling of the US and Chinese economies is bad news for Germany. Quantitative decoupling would be worse. Berlin must adopt a more pro-active approach to managing German and European economic vulnerabilities as well as enhancing its geo-economic power.

> German dependence on Russian energy imports constrains Berlin’s economic and political room for maneuver. Germany’s dependence on China and the United States are quantitatively if not qualitatively even more significant. US-Chinese geostrategic conflict and economic decoupling will expose Germany’s vulnerabilities.

> At the national level, Germany needs to take a more strategic approach to managing its economic vulnerabilities by identifying, monitoring and mitigating them in a systemic manner.

> At the EU level, Germany must push for the greater mobilization of the bloc’s latent economic power. The EU should also consider moving beyond its present deterrence- to a more compellence-oriented geo-economic policy.

Gee-economic Power and Economic Statecraft

The weaponization of economic interdependence involves the exploitation of asymmetric vulnerabilities.[1] Geo-economic power, including the credibility and effectiveness of threats, hinges on the relative greater costs country A can impose on country B. Efficacity in terms of successful coercion, whether in the form of deterrence or compellence, hinges on how willing and able country B is to absorb the costs resulting from country A’s actions. Economic statecraft refers to a government’s intentional, public and purposive management of its trade, financial and currency policies to advance economic and political objectives.

Trade power is a function of country A’s ability to exploit country B’s relative dependence on country A’s imports and exports. Financial power is a function of country A’s ability to exploit country B’s relatively greater dependence on country A’s financial market. Currency power, closely related to financial power, reflects the extent to which country B depends on the use of country A’s currency for international trade and financial transactions. Dependence, as opposed to reliance, implies high substitution costs from the point of view of country B. Asymmetric dependence (or asymmetric vulnerability) refers to the fact that country A depends less on country B than vice versa and hence incurs relatively lower costs in case bilateral economic interaction is restricted. As explained elsewhere, the ability to exploit asymmetric interdependence may be effective in terms of imposing relatively greater costs on a country without necessarily being efficacious in terms of coercion.[2]

A low degree of trade dependence, large, liquid and open financial markets and the widespread use of the dollar in international trade and finance provide the United States with significant geo-economic power. The fact that the world’s major countries are relatively dependent on the American economy also allows Washington to make bilateral measures more effective by extending them to third parties in the guise of secondary sanctions. This is often necessary to prevent third parties (‘third-party spoilers’) from undermining US measures. The ability to impose secondary sanctions rests on the desire of third parties to maintain maximum access to US markets. The economic costs of complying with secondary sanctions are almost always smaller than the costs arising from US market exclusion. China may be the largest trading partner for more than a hundred countries, and this provides it with bilateral geo-economic leverage. It is its continued trade dependence on the United States, less so on Europe, as well as its dependence on the US dollar that makes it vulnerable to US geo-economic coercion.

Sources of American Geo-Economic Power

A large market for imports and the production of difficult-to-substitute (‘strategic’) exports confers ‘trade power.’ Washington has taken advantage of other countries’ trade dependence to ‘good’ effect in the sense of successfully coercing trading partners, like Japan in the 1980s or China more recently. It was America’s relative limited export dependence that underpinned its influence during the international currency conflicts of the 1980s. Moreover, the dollar’s wide-spread international use confers ‘currency power’.[3] Washington successfully used dollar sanctions, and the threat thereof, to coerce Iran and largely nudge third parties into compliance with US policies. More recently, the United States (and other American allies) froze the Russian central bank’s dollar assets, imposing significant economic and financial costs on Moscow.

What underpins US currency power? First, as an international currency, the dollar serves as a medium of international exchange. The private sector engages in FX trading and settlement, and the official sector (central bank) uses the dollar for intervention purposes. Second, as an international currency, the dollar serves as a unit of account with the private sector using it for trade invoicing purposes and many central banks as an anchor currency. Third, as an international currency the dollar serves as a store of value in the guise of financial investment in the case of the private sector or FX reserves in the case of the official sector.

And what underpins financial power? First, foreigners need to hold liquid dollar assets to engage in international trade and financial transactions. Second, the US financial markets are the deepest and most liquid in world, in addition to being very open and sophisticated, providing foreigners with unmatched opportunities to trade, invest, raise and hold funds. Currency and financial power go hand in hand.

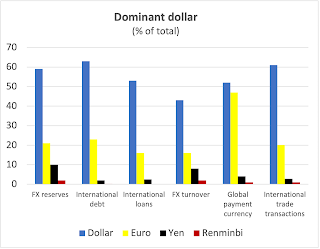

The dollar is the dominant international currency with the euro as distant second and the renminbi nowhere to be seen for now. The dollar is particularly dominant with respect to international financial transactions, less so with respect to trade-related transactions. But international financial flows exceed trade flows several times. Bank of International Settlements put it succinctly:

Although the United States accounts for one quarter of global economic activity, around half of all cross-border bank loans and international debt securities are denominated in US dollar. Deep and liquid US dollar markets are attractive to non-US entities because they provide borrowers and lenders access to a large set of countries parties The preeminence of the US dollar as the global reserve currency and in trade invoicing further motivates its international use.[4]

Dollar Dominance Confers Power to America

Nothing demonstrates the importance of the dollar more than the fact that 90% of the time it is on one side or the other of foreign-exchange transactions, compared to 30% and 4% in the case of the euro and the renminbi, respectively. (The total adds up to 200%, as two currencies involved in every foreign-exchange transaction.)[5] If one wants to convert Chinese renminbi into Brazilian reais, one typically needs ‘trade through’ the dollar. Moreover, 80% of ‘international’ trade (roughly: between non-US and non-euro area economies) is denominated in dollars. Therefore, denying another country to use of the dollar makes it very costly, if not impossible for this country to engage in international transactions. Threatening third parties, for all intents or purposes, then largely cuts a country off dollar-based international finance and trade.

The need to hold dollar liquidity to engage in international transactions also renders a country vulnerable to asset freezes and other financial restrictions. It is comparable to an individual holding most of its liquid savings in the form of deposits at a single commercial bank and the bank then restricts access to the deposits. Ironically, it is a reserve-currency country’s foreign liabilities that give it power, and it is a non-reserve-currency country’s foreign assets that make is vulnerable to financial restrictions.

Why then do foreigners choose to hold dollars (and other international currencies) if it makes them vulnerable to financial and currency statecraft? Answer: convenience, cost, lack of viable alternatives, credibility, trust, network effects. Naturally, over-using the ‘currency weapon’ and financial sanctions chips away at trust, particularly in the eyes of geopolitical competitors. But although non-reserve-currency countries may be reluctant to hold dollars (or other reserve currencies), in practice they have little choice due to a lack of viable alternatives. The weaponization of international financial and currency relations will nonetheless make non-reserve-currency countries more circumspect, particularly if they see the US as a geo-political antagonist.

The demise of the dollar as the dominant international reserve currency has been foretold many times. Thus far, its attractiveness has endured, not least because international currency competition can be likened to a ‘reverse beauty contest.’ Even if the dollar becomes less attractive, it will remain dominant for lack of alternatives. For the foreseeable future, neither the euro nor the renminbi will replace the dollar. The dollar’s importance as a reserve currency (international currency held by central banks) has declined somewhat, but this decline has benefitted lesser international currencies rather than its two most obvious challengers, the euro and the renminbi.[6] The United States will therefore retain significant currency and financial power, even as this will incentivize Europe and especially China to enhance the international role of their currencies.

Germany (Less So the EU) Is Geo-Economically Constrained, Vulnerable

In terms of trade, Germany is, not surprisingly, substantially more dependent on exports to China and the United States than vice versa. However, China’s export dependence on both the EU is roughly comparable Germany’s dependence on China. To the extent that Germany can successfully mobilize the EU’s latest economic deterrence potential in the guise of the proposed anti-coercion tool, this will help shield Germany from Chinese geo-economic coercion in the guise of import restrictions by creating the economic equivalent of mutually assured destruction. In fact, the EU as a block is slightly less dependent on China than vice versa. Meanwhile, the United States is far less dependent on both the EU and China in terms of exports and import volumes. This is an important dimension of US geo-economic power. [7]

In terms of import dependence, the US produces several ‘strategic’ goods, such as semiconductors, that China relies on more than the EU. At the same time, China also exports certain ‘strategic’ commodities that both the EU and America depend on, such as rare earths. Establish precisely who depends more on whom here requires a careful and detailed economic analysis, which is beyond the scope of this Policy Brief. However, the reach of US secondary sanctions combined with albeit limited availability of rare earths outside China tilts the balance in America’s favor. Chinese export restrictions might raise prices, but both the US and the EU would find third-party suppliers. China will find it considerably more difficult to procure advanced semiconductors and other advanced technology. Other country’s import dependence also provides the United States with geo-economic power.

In terms of finance, German foreign direct investment (FDI) in China and especially the United States is far greater than respective Chinese and American FDI in Germany. This is true when measured in dollars and, more relevantly, as a share of gross domestic product. In purely financial terms, this makes Germany relatively more vulnerable vis-à-vis potential Chinese and American restrictions than vice versa.[8] The EU-US FDI relationship is substantially more balanced. American FDI in China and Chinese FDI in America are roughly comparable in size (leaving aside data quality issues). To the extent that foreign direct investment is integral to overseas supply chains, any disruption will have an impact that might go far beyond financial losses. But this, too, is difficult to establish with much precision, absent painstaking economic research.

Varying financial vulnerability is also reflected in the fact that nearly half of US financial assets as well as government debt is held by non-residents (mostly central banks). China is the second-largest foreign holder of US government debt after Japan, according to US Treasury data, to the tune of > $ 1 trillion. (In reality, it is probably the largest single largest holder of US treasuries due to reporting issues.) By comparison, foreigners hold only 3-5% of Chinese government bonds, and this constitutes a far smaller share of their foreign holdings. This makes China more vulnerable to a freeze of its US assets than vice versa. And more importantly, an asset freeze would not just lead to financial losses but would also make more complicated the use of the dollar for international transaction purposes.

The euro is the world’s second most important international currency after the dollar. Most euro area exports are invoiced in euros.[9]. The dollar dominates trade in all regions, except for Europe. China, despite being the largest trading partners for a hundred-odd countries, remains highly dependent on the dollar for trade purposes, not to mention international financial transactions. Europe is relatively less dependent on the dollar than China, but it is more dependent on the dollar than the US is on the euro. Importantly, the willingness of the United States to make ‘liberal’ use of the ‘dollar weapon,’ including secondary sanctions, by targeting individual companies make the dollar weapon quite effective. Individual companies would rather forego business with the sanctioned country than be prevented from using the dollar, given its importance. The euro area would need to be able and willing to threaten retaliation in the form of countervailing euro sanctions to deter dollar sanctions. Politically and economically, it has thus far been unwilling and unable to do so, not least because of the costs European companies would incur in case ‘currency deterrence’ fails.

In brief, Germany’s relative trade and financial vulnerability is considerable. China and America are Germany’s two most important trading partners. Last year, China and America accounted for 8% and 9% of German exports and 12% and 6% of total imports, respectively. Trade-wise, Chinese and US dependence on Germany is significantly lower. Based on FDI (much less so based on consolidated bank lending),[10] Germany also holds significantly larger assets in the United States and China than vice versa. And German FDI in China is greater in both dollar and gross domestic product terms than Chinese investment in Germany. All around, Germany is more vulnerable.

It is therefore imperative that Germany pushes more forcefully for the mobilization of the EU’s latent economic power to offset its vulnerability. Starting with the macro-vulnerabilities discussed, it should identify more granular national and EU-level economic vulnerabilities and search for cost-effective ways of mitigating them to preserve greater geopolitical autonomy as well as minimize the economic costs of a broader geo-economic confrontation. Energy dependence aside, the fallout from a breakdown of economic relations with China in, for example, the context of a military conflict over Taiwan would be far greater than the costs incurred due to the Ukraine war. Such a conflict might also severely constrain the choices of German and European policymakers, not least because the United States would find it difficult to accept it if its European allies maintained commercial relations with China, while it is engaged in a military conflict with the Beijing. (If the US navy were to block Chinese seaborne trade, all bets would be off, either way.)

How China and Europe Are Addressing Their Vulnerabilities

The weaponization of international economic relations makes the major power increasingly uncomfortable in terms of mutual dependencies, whether in terms of trade, finance, currencies or technology. China, the EU and the United States are all are keenly aware of their respective bilateral dependencies and concomitant vulnerabilities. The Russia sanctions served as a reminder, if one was necessary, of just how costly such vulnerabilities can be.

As the geo-economically mightier country, the United States is perhaps more, or at least equally, concerned with how best to leverage its power than with patching up its vulnerabilities. It has taken advantage of its geo-economic tools to slow down technological diffusion to China and limit the extent to which US trade and investment relations contribute to China’s technological and military ascent. To the extent that the US is concerned about geo-economic vulnerabilities, it is primarily about dependence on strategic imports from China, such as rare earths, and only secondarily American financial investment in China.[11] Meanwhile, China and Europe are more concerned with how to patch up their vulnerabilities vis-à-vis each other and the United States. One side’s vulnerability is the other side’s leverage.

China’s Quest to Create Alternative International Economic Regime

China has begun to lay the foundation of an alternative or parallel international economic regime to reduce its dependence on a largely US-dominated system and network. In terms of trade, China is seeking to reduce its dependence on the rest of the world, and especially the United States, as reflected in its ‘dual circulation’ and Made in China 2025 policies. Its trade policy, including the recent agreement on the Asia-Pacific-focused Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership and its application to the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, are aimed at diversifying trade relations away from the United States, and perhaps create more Sino-centric regional trade relations.

Policies aimed at laying the groundwork of a quasi-parallel international financial regime, including the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Belt Road Initiative, also needs to be seen in the context of reducing Chinese dependence on a regime where the US plays a very influential, even dominant role. It also offers the possibility of promoting the renminbi as an international currency, as does the creation of an e-yuan and a renminbi-based interbank payment systems as well as the provision of renminbi swap lines[12] and the political push to get the renminbi added to the IMF’s special drawing basket. Taken together, these initiatives can be though to constitute a strategy aimed at enhancing the role of the renminbi in the international economy.

Despite all this, China has made only limited progress in terms of challenging the dominance of dollar. [13] This is largely attributable to lack of an open capital account, underdeveloped domestic financial markets as well as concerns about the rule of law and, for some countries, geopolitical risk, all of which severely curtails the attractiveness of the renminbi as an international currency. Progress on financial reform will remain slow given that it would bring about the demise of China’s long-standing economic development model at a time when concerns about rebalancing and the build-up of financial risks preoccupy policymakers.

China remains highly dependent on the dollar. (It also remains an ‘immature creditor’ in that it is forced to hold its foreign assets in non-RMB-denominated instruments, namely US government and agency bonds.) Combined with China’s relative greater dependence vis-à-vis the US in terms of trade, this continues to make Beijing susceptible to US geo-economic and geo-financial coercion. China nonetheless has the structural-economic potential to become the world’s dominant reserve-currency issuer.

The EU has also recognized its vulnerability in context of the weaponization of interdependence and has proposed a so-called anti-coercion instrument to lessen its vulnerability vis-a-vis third-party coercion.[14] Calibrating such a geo-economic deterrence policy in terms of delegation and parameters will be challenging. And if deterrence fails, the EU needs to be willing to retaliate if it is to preserve its credibility. Despite these challenges, Germany should push more forcefully for the EU to mobilize its latent power by creating instruments that enhance its ability to make use of its geo-economic power.

In terms of export dependence, the EU can largely hold its own, given the importance of its market to third-party exporters. This is certainly true for China, but somewhat less so for the United States. The EU has also recognized its dependence on critical imports, and not just in the wake of the Ukraine war. In terms of energy dependence, various trade- and domestic market-related measures have been proposed, including joint purchases. It also seeks to address its import-related vulnerabilities through import diversification and intra-alliance cooperation (‘friend-shoring’) and, if necessary, more costly re-shoring. In terms of friend-shoring, the EU is also engaging in bilateral consultations with its American alliance partner to address common supply chain risks and seek joint mitigation policies. The EU has the necessary financial resources to mitigate import-related dependencies. The challenge is to agree on the necessary policies and the related distribution of costs and benefits.

In terms of currency power, the euro has a sizeable presence in international markets but continues to suffer from structural shortcomings compared to the dollar. While the euro area members are committed to ‘completing’ banking union and the EU to pushing ahead with capital markets union, this will not suffice to make the euro co-equal to the dollar. The euro area needs to strengthen monetary union through well-designed fiscal integration. Only then will the euro gain sufficient credibility, and the euro area will be able to issue enough safe, risk-free sovereign assets to rival the dollar. Reform should be complemented by the creation of a capital markets union to create deeper and more liquid capital markets and the completion of banking union, including a credible financial backstop. The euro area members are moving in the right direction but severing the sovereign-bank nexus through a deepening of banking union and half-hearted attempts to promote truly European capital markets will not be enough if the goal is for the euro to become serious competitor to the dollar to mitigate European currency vulnerabilities.

Creating a credible and effective geo-economic tool, pro-actively managing import-related vulnerabilities, and turning the euro into a credible alternative to the dollar would go a long way in mitigating politically exploitable geo-economic vulnerabilities. All these measures are meant to reduce aggregate vulnerability and to enhance geo-economic deterrence to reduce the risk of geo-economic conflict and retain geopolitical room for maneuver.

But Germany and the EU should not just think in terms of patching up vulnerabilities and deterring geo-coercion. Logically, it should also think about how best to mobilize its latent power for less defense, deterrence-oriented goals. Aside from the fact that retaliation against geo-economic coercion is itself a form of compellence, the EU should think more broadly at the possibility of mobilizing its potential not just in terms of ‘power-as-autonomy’ but also in terms of ‘power-as-influence.’ The primary goal should be to deter geo-economic coercion and maintain geopolitical room for maneuver. But the EU should also seek to leverage its influence where asymmetric interdependence is in its favor to help bring about outcomes it desires. Precisely to what end EU geo-economic power should be used will of course prove very contentious among the EU-27. (This idea will be pursued and elaborated upon in a future Policy Brief.)

In addition to supporting efforts to enhance the ability of the EU and the euro area to exercise geo-economic power, Germany should create a National Economic Security Council tasked with identifying, monitoring economic-financial vulnerabilities at the national level and proposing cost-effective mitigation policies. Monitoring and policies must be coordinated with EU partners. National policies will reflect national priorities. But the coordination of national policies is essential to avoid duplication, enhance efficiency and overcome collective action problems in terms of mitigating EU-wide vulnerabilities. A highly integrated European economy makes the close coordination of national mitigation policies indispensable.

For a country as dependent on the international economy as Germany, more so than for other countries, national security and economic security are merely two sides of the same coin. This urgently calls for the closer coordination of foreign and foreign economic policies at the national level. As the Ukraine war demonstrated, foreign economic policy and foreign policy are closely intertwined. They must be devised and pursued in close coordination with one another. And this requires creating the necessary national-level institutions to facilitate strategic planning, mitigation and implementation. The creation of national security council is overdue. The creation of a national economic security council or its equivalent is, too. Other ‘middle powers’ such as Japan and Korea have already created council and bodies tasked with identifying and managing geo-economic risks.

[1] Daniel Drezner, The uses and abuses of weaponized interdependence (Washington 2021).

[3] Currency and financial power need to be distinguished from ‘macro-foundational monetary power,’ which consists of a country’s capacity to delay and/ or deflect the costs of balance-of-payments adjustments. financial flows. See Benjamin Cohen, Currency statecraft (Chicago 2019). Other sources of trade and financial power statecraft include the provision (withholding) of official financing as well as official purchases of goods and services (or their cancellation).

[4] BIS, US dollar funding, CGFS Paper 65, 2020, p.1: https://www.bis.org/publ/cgfs65.htm (last accessed: April 27, 2022). BIS, Global dollar credit, Working Paper 483, 2015: https://www.bis.org/publ/work483.htm.

[5] European Central Bank, The international role of the euro, 2021: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/ire/ecb.ire202106~a058f84c61.en.pdf.

[6] This is probably best explained in terms of reserve managers desire to diversify their investment returns rather than an attempt to engage more actively in non-dollar based international currency transaction. IMF, The stealth erosion of dollar dominance, Working Paper 58, 2022: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/03/24/The-Stealth-Erosion-of-Dollar-Dominance-Active-Diversifiers-and-the-Rise-of-Nontraditional-515150.

[7] Technically, gross exports are an imperfect measure of dependence. Value-added embedded in exports as well as the ability direct exports to third markets at low cost. The same applies even more to import-related vulnerabilities. Import volumes are an even poorer indicator of import dependence as far the potential of ‘strategic’ imports to cause economic disruption are concerned. An economy suffering from shortages of energy, rare earths or semiconductors, for example, may suffer tremendous economic dislocation.

[8] Data on FDI and non-FDI assets and liabilities are not very reliable, as it is often difficult to determine who the ultimate creditor or debtor is. Data on non-FDI investment is especially murky, except for bank lending. See BIS, Consolidated banking statistics, 2022. Note that non-FDI is typically more liquid than FDI. Therefore, less risk should at the same notional amounts of exposure. Naturally, all economic data are mere proxies of actual economic, much less political vulnerability. BIS data suggest that German bank claims on the US are $446 billion compared to a mere $21 billion on China. BIS does not publish Chinese claims on Germany or the US. According to the Bundesbank, German FDI in the US and China amounts to €411 billion and €89 billion, respectively. BIS, Consolidated Banking Statistics: https://www.bis.org/statistics/consstats.htm

[9] ECB, Patterns in invoicing currency in global trade, 2020: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2456~540fd64604.en.pdf..

[10] BIS, Consolidated Banking Statistics: https://www.bis.org/statistics/consstats.htm

[11] White House, Building Resilient Supply Chains, Revitalizing American Manufacturing and Fostering Broad-Based Growth , 2021: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/100-day-supply-chain-review-report.pdf.

US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Report to Congress 2021, 2021: https://www.uscc.gov/annual-report/2021-annual-report-congress.

[12] IMF, Evolution of bilateral swap lines, Working Paper 210, 2021: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2021/08/06/Evolution-of-Bilateral-Swap-Lines-463358.

[13] Markus Jaeger, Yuan as a reserve currency, Deutsche Bank, 2010: https://www.dbresearch.com/PROD/RPS_EN-PROD/Research_Briefing%3A_Yuan_as_a_reserve_currency%3A_Lik/RPS_EN_DOC_VIEW.calias?rwnode=PROD0000000000454704&ProdCollection=PROD0000000000480994.

[14] Markus Jaeger, Designing geo-economic policy for Europe DGAP Policy Brief, 2022: https://dgap.org/en/research/publications/designing-geo-economic-policy-europe.