The unipolar moment has passed. Washington and Beijing are fully engaged in great power competition.[1] If competition is the consequence of China’s rise and America’s relative decline, then China’s future economic growth trajectory will be a major factor driving geo-strategic rivalry.[2] It is therefore worth exploring how quickly and to what extent China’s economic power will grow in the coming years. Power and influence in international politics is of course not simply a function of economic size. But economic size matters greatly. The redistribution of economic power in the international system also informs the strategies pursued by China and the United States. The course and likely outcome of US-Chinese competition, in turn, should inform Europe’s and Germany’s strategy and policies.

Power Shift As Driver of Strategic Competition

Power transition theory posits that “(a)n even distribution of political, economic, and military capabilities between contending groups of states is likely to increase the probability of war; peace is preserved best when there is an imbalance of national capabilities.”[3] If war is seen as simply a more intense form of competition, the theory implies that the risk of intense American-Chinese competition will remain very high in the next few years: the American and Chinese economies are very comparable in size.

The rise and fall model of international politics identifies the factors driving the ascent and decline of great powers. According to Paul Kennedy, dominant countries wind up in a situation of ‘imperial overstretch,’ where their military-economic commitments exceed their ability to maintain them, leading to their subsequent decline (or defeat). Along similar lines, Robert Gilpin posits that states rise until the costs of expansion exceed its benefits. States later start to decline as the costs of maintaining dominance exceed the ability to generate sufficient resources to cover those costs. Rising states reach this inflection point because their economic growth is subject to the ‘law of diminishing returns,’ and both public and private consumption outpaces economic growth. This leads to insufficient investment, increasing indebtedness, sub-par growth, and relative economic decline.[4]

Indeed, US real GDP growth has declined to less than 2% in the past decade. Government debt amounts to nearly 100% of GDP and is projected to reach almost 200% of GDP three decades from now.[5] The United States is also the world’s largest international debtor in dollar terms, and its net international liabilities exceed 60% of GDP. By comparison, China’s economic growth, though slowing, has averaged more than 6% over the past decade. Government debt is about 50% of GDP (though, admittedly, this does not account for significant off-balance sheet liabilities). China is also one of the world’s largest international creditors with net international assets of around 20% of GDP. This is consistent with Gilpin’s model: a fast-growing, investment-oriented China is rising rapidly, while consumption-oriented and productivity-constrained America is in relative decline.

These models do not capture all the major factors affecting great power rivalries. But the focus on the costs and benefits of expansion as well as the capacity to generate sufficient resources to withstand or prevail in geopolitical competition offers a heuristically valuable framework to analyze the medium- and long-term dynamics of great power competition. The availability of resources also informs, if not determines, the strategic choices available to both rising and declining powers.

US-led alliances retain economic edge – for now

China has been ascendant and the United States has been in relative decline. For the time being, the United States and its alliance partners in Asia and Europe are holding their own in terms of economic size. The gross domestic product (GDP), measured in PPP terms, of European NATO allies (including Finland, Sweden and Canada) exceed Russia’s by a factor of six. The combined GDP of Germany, France and the UK alone exceeds Russia’s by a factor of 2.5.

In Asia, the United States and its treaty allies (Japan, Korea, Philippines, Australia, Thailand) account for a larger aggregate economic output than China. But China’s economy is already larger than America’s, and China’s economy is on track to overtaking the combined GDP of the United States and its allies by 2030 or so. If, however, one adds Washington’s emerging (or emerged) Indo-Pacific ‘security partners’ (India, Taiwan, Vietnam) to the balance, America’s position looks more competitive. Of course, the contribution of these countries’ economies to aggregate alliance GDP would need to be appropriately discounted to reflect their less certain alignment with Washington’s strategy.

This is simply snapshot of where things stand today. The key question is whether and to what extent China’s economic ascent will continue.

Aggregate economic size is only a proxy of economic and political power. Economic power needs to be converted into international political power, and economic power may be converted more or less efficiently.[6] Aggregate national income does not translate into power one to one. Politically, a government may be constrained in terms of extracting resources in support of international political goals. If an economy is large but is not capable of producing high-technology weapons, for example, economic size fails to translate into relevant political power. Economically, size does not equal size. All other things equal, a large economy with a low per capita income allows governments to extract relatively fewer resources (or reduce private consumption less) than similarly sized economies with which higher per capita incomes. A US-China comparison can serve to illustrate this.

In PPP terms, China is larger than the United States. But America’s per capita income level is three-and-a-half times higher than China’s. Per capita income in the United States is $70,000, compared to $20,000 in China. Economically, if not necessarily politically, the United States may be able to mobilize $50,000 of per capita income to support geo-strategic competition, leaving $20,000 for household consumption. But China may only be mobilize $10,000, before reducing household consumption to unsustainable levels of less than $10,000. China would then only be able to mobilize half its total GDP, while the US would be able to mobilize 5/7 of a smaller GDP. In this hypothetical example, the US would be able to mobilize more resources, even though its economy is smaller than China’s. The degree of resource extractability matters.

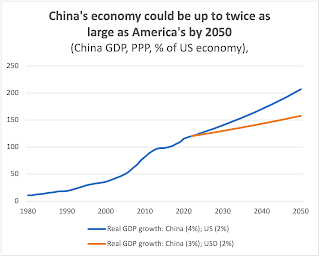

China’s economy may be up to twice as large America’s economy by 2050

With this caveat in mind, it nevertheless worth looking at China’s future growth trajectory. First, some historical context. China’s economic ascent, while impressive, is not without precedent. Japan and Korea, for example, experienced high economic growth, allowing them to (almost) ‘catch up’ with advanced economies. Japan’s per capita income reached 90% of America’s in 1990 (but has since fallen dramatically). Similarly, Korea has seen its per capita income as a share of US income double from 35% to 70% between 1990 and 2020. By comparison, China remains a laggard, even though four decades of very high, double digit real economic growth has lifted China’s per capita income to a respectable 30% of US income.

More recently, Chinese growth has slowed. Ten-year real growth has fallen form 10% in 2014 to 6% in 2022. The IMF projects growth of 4.5% in 2023-27. (The Chinese government has just lowered its growth target for 2023 to “around 5%” from 5.5% last year, confirming the downward trend.) By comparison, the IMF forecasts US growth to average 1.8%, meaning Chinese growth will exceed US growth by a factor of 2.5. This is substantial, but not as dramatic as it once was.

China’s economic development model has relied on high savings and high investment. But an increasingly inefficient allocation of investment is today translating into lower productivity and slower economic growth. Such a deceleration is to be expected, as a country becomes richer. Countries are at risk of getting caught in the so-called ‘middle-income trap,’ which often leads previously fast-growing economies to experience a substantial downward shift of their growth rate.

To overcome or sidestep the trap, governments need to adjust their economic policies. Here, Beijing‘s tightened political control over parts of the domestic economy and the securitization of foreign economic relations will be decidedly unhelpful. Demographics as well as financial risks related to the infrastructure-focused growth model and directed bank lending also represent important risks to the economic outlook. China’s medium-term growth outlook faces significant challenges.

China could be doing better, given its per capita income levels. Korea’s ten-year economic growth rate only fell to 2% by the time per capita incomes reached 70% of US income. But in the early nineties, when Korea’s per capita income as a share of GDP was comparable to China’s today, it managed generate 9% growth.

A simplistic (and technically somewhat dubious) extrapolation that assumes Chinese growth of 4% and US growth of 2% shows that the Chinese economy will be about twice as large as America’s by 2050. If China grows 3%, its economy will one-and-a-half times the size of America’s. Adjusting for projected population changes, this would put China’s per capita income at a less 2/3 of Americas – or roughly where Korea is today. A plausible number. It took Korea three decades to get to 70% of US income from 35% (see chart above). So for Chinese per capita income to move from 1/3 to roughly 2/3 of US income looks like a plausible scenario. If one assumes, as happened in the case of Korea, that China’s growth rate will decline from 4.5% today to 2% in 2050, China’s will be a little more than one-and-a-half times the size of America in thirty years.

Strategic behavior of rising and declining states

Barring major economic, financial or political accidents, China’s economy will be 50-100% larger than America’s. If one adds back in US allied GDP and adjusts for ‘resource extractability’ (or differences in per capita income), China will still have an edge, but it will not be so overwhelming that it leaves Washington no choice but to fold strategically. But it will mean that Washington will be forced to direct the bulk of its resources to Asia (with obvious consequences for European security). Where does such a scenario will US and Chinese strategic options?

At the highest (and least interesting) level of abstraction, strategy (or grand strategy) can be geared toward expansion, stability or retrenchment. Historically, rising powers tend to expand, declining powers tend to be forced into retrenchment. The logic is simple. Rising powers see their interests expand as well as their ability to realize these expanded interests. A rising power’s economic ascent allows it to convert increasing wealth into international political power and pursue its goals more assertively, often with a view of gaining greater control of their geo-strategic and economic environment.[7]

By contrast, declining powers are faced with a growing imbalance between their ability to defend their existing interests and the means available to do so – not least because of the greater means available to and the more assertive behavior of rising powers. Growing resource constraints make maintaining existing commitments more difficult. Rising powers therefore tend to be revisionist, while declining powers are status quo oriented, which often leads to tensions, competition and conflict. Competition is even less avoidable in a broadly bipolar system because it makes so-called ‘buck passing’ impossible.[8] (Buck passing refers to the tendency of countries to avoid confrontation with a rising power in the hope that other countries will counter its rise.)

Strategic Options of Declining Powers

Rising powers can expand and become more assertive, or they can bide their time. Following MacDonald and Parent, [9] declining powers have several strategic options to deal with an adversely shifting balance of power and growing resource mismatch. Expansion, historically often accompanied by preventive or preemptive war; an aggressive, is a security-focused strategy to halt or reverse relative decline by militarily defeating the rising power (or coalition of powers). It is associated with the aggressive mobilization of residual resources. Bluffing consists of denying one’s decline or overstating one’s strength. It is associated with inertia in terms of resource generation, Binding seeks to increase the predictability and legitimacy of the existing international system by strengthening existing institutions, rules and norms. Resources are deployed in support of diplomacy rather than security. Retrenchment is characterized by a realignment of means and ends in an attempt to maintain ‘strategic solvency.’[10] It is generally the best option available to a declining power, even though this strategy can be politically difficult to implement

Finally, appeasement recognizes one’s decline, but beats a precipitous retreat through sustained asymmetric concessions to rising power in the hope of achieving peace and security

In practice, strategic choice will be influenced by whether a country believes it is in relative decline, whether it believes it can reverse decline, and whether it expects its rival to continue to rise. A state’s assessment of its present and likely future position matters.

Moreover, declining powers do not necessarily face a rising power on its own. An option MacDonald and Parent do not include in their menu of options is that of a declining power seeking to counter a rising power through a combination of ‘external’ and ‘internal balancing’. Internal balancing refers to the domestic mobilization of resources in support of international balancing. External balancing involves the mobilization of allied resources to balance, or even defeat, a rising power. This is effectively, the strategy Washington has adopted. [11]

Washington depends on allies for successful defense of the status quo

Maintaining the status quo in Asia is Washington’s strategic priority. America’s strategic goals have not changed much since it came of age as a great power in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Preventing another power from dominating either end of the Eurasian landmass, which might exclude America economically and would allow for the emergence of a strategic threat, remains a vital strategic interest. The United States has fought one and arguably two world wars as well as a cold war in pursuit of this goal. China’s rise represents a threat to US strategic interests.

America’s relative position relative to China will weaken in terms of resources. But rather than realigning means and ends (retrenchment), a combination of internal and external balancing holds out the prospect of ‘holding the geopolitical line.’ Washington is faced with a shifting distribution of power, but its geopolitical overstretch is manageable, provided it maintains the cohesion of its alliance system in support of its status quo strategy. Washington’s actual commitment to defending its position in East Asia may or may not be what is sometimes referred to as ‘imperial afterglow.’[12] But, strategically speaking, it is an approach that while facing challenges has a fair chance of success.

Washington benefits from long-standing alliances and emerging partnerships in Asia, including formal treaty allies (Japan, Korea, Philippines, Australia, Thailand), and countries that have adversarial relations with China (India, Taiwan, Vietnam etc.). The United States also leads the world’s largest and most powerful military alliance, NATO, which regards China as a ‘challenge.’ Washington has no territorial claims in the region, it is committed to defending the territorial status, and maintaining the status quo and the balance of power aligns with the goals of virtually all countries in the region other than China, and particularly those involved in territorial or maritime disputes with China.

By comparison, China has only one formal ally (North Korea) and it only has close diplomatic ties with economically insignificant countries (Laos, Cambodia). It is true though that Beijing has moved closer to Moscow. This is significant. Chinese access to Russian energy, commodities and military technology matters. But resource-wise, Russia does not add much to China’s economic weight or the balance of economic power in Asia: Russia’s economy is relatively small; its long-term growth outlook is dismal due to sanctions and demographics; and most of Russia’s resources will be deployed to Europe, not East Asia.

For the time being, the United States and its regional treaty allies have a combined GDP larger than China, Russia, North Korea, Laos and Cambodia combined. This will change provided China manages to maintain a reasonably high growth rate over the next few decades. Another caveat is that the United States has global commitments, while China can afford to largely focus its resources on the Indo-Pacific region. This means that Washington will be increasingly forced to shift its resources to Asia. It also suggests that Washington will try to work hard to bring other countries to join its alliance, formally or informally in order to preserve the balance of power and resources in the region.

Alliances also allow the United States to take advantage of East and South-East Asia’s maritime geography. The US alliance system effectively controls the first and second island chains as well as important choke points within them. In military-logistical terms, however, Washington faces the ‘tyranny distance,’ which would be a particularly challenge in the event of a military conflict. This is one more reason why the alliance system is absolutely essential to US strategy. Without allies, Washington’s position in East Asia would become untenable, economically and militarily.

Although China’s rise points to retrenchment being the best strategy for the United States, a well-managed alliance strategy can largely, if not completely offset China’s increasing resources and more assertive policies. Washington’s alliance-focused strategy to counter China’s rise has a fair chance of being successful in terms of maintaining the territorial and political status quo in Asia and preventing Asia from falling under Chinese dominance.

Unless it attracts allies, Beijing will find it difficult to revise the status

China’s geo-strategic position is vulnerable, not least due to China’s dependence on access to world markets in terms of critical goods, such as energy and food. In line with its expanding interests and the ability to defend them more assertively, China is seeking to push out the security perimeter by way of territorial claims and ‘island building.’ The establishment of a network of commercial and military facilities throughout the Indian Ocean (‘string of pearls’ strategy) is meant to strengthen its ability to protect its seaborne lines of communication and foreign trade. China’s expanding naval capabilities, including the shift from a ‘brown water’ to ‘blue water navy’ as well as from near-shore defense to far sea protection need to be seen in the same light.

Alliances are a key US strength and thus make them a Chinese target. Economically and geo-strategically, the United States can ill-afford to lose allies in Asia. China’s best strategy is therefore to pick off US allies and cast doubts on US commitments to defend the status quo in the region. Losing an ally or failing to defend the status quo might prove catastrophic to America’s position. This is why the focus of Chinese and US policymakers is on Taiwan, for it is a key element of the regional security architecture. Beijing’s focus on Taiwan makes strategic sense. Beijing is also focused on strengthening its position in the India Ocean to secure energy imports as well as the Pacific east of the second island chain, where Beijing and Washington are vying for the support of Pacific Island countries.

Beijing’s greater geo-political and geo-economic assertiveness has made many countries in the region more apprehensive about China’s rise, but it has also signaled China’s ability and willingness to exert greater influence. Given their growing dependence on the Chinese economy, countries in the region do not want pick a fight with China, if they can help it, nor do they want to be forced to pick sides between the United States and China. It is no coincidence, however, that countries that are most directly involved in territorial disputes with China or feel most directly threatened geographically by China’s rise, are, on average, more closely aligned with Washington.

Due its sheer and growing economic weight, countries in the region will become more dependent on China. Beijing has flanked its rise with various geo-economic initiatives, which make China relatively less dependent on the outside, while making countries in the region relatively more dependent on China. The Belt and Road Initiative helps integrate parts of South and South-East Asia in terms of infrastructure and facilitate China’s access to vital resources. Made in China 2025, China Standards 2035 and the ‘dual circulation’ strategy are meant to make China less dependent on other countries. Currency internationalization and regional trade integration in the guise of, for example, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, are meant to turn China into the regional hub and diminish the economic importance of the United States. All these policies seek to integrate countries in the region into Chinese-centered or -controlled networks and weaken their economic links with the United States.

China-led regional economic integration exploits Washington’s failure to complement its national security and Indo-Pacific alliance strategy with a stronger economic component. Initiatives such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and Quadrilateral Security Dialogue fall short of providing countries in the region with what they desire and need the most: access to another large, overseas markets to mitigate their growing economic dependence on China.

Growing economic, financial and even technological integration, combined with China’s growing economic and financial weight, will exert a substantial economic pull on countries in the region, relative to the more slowly growing US economy. To the extent that China’s economy becomes relatively less dependent on the outside world, it will gain greater geo-economic leverage vis-à-vis other countries, especially in in East and South-East Asia, making their strategic position more intractable. Ultimately, however, security concerns will override economic interests. Beijing’s greater assertiveness will therefore play into the hands of Washington’s interest to strengthen its alliance and maintaining the status quo.

[1] Ethan Kapstein & Michael Mastanduno, Unipolar politics (New York 1999)

[2] If one subscribes to some version of ‘democratic peace theory’, it is plausible to envision a scenario where such competition can be avoided, namely in case China turns into a democracy. The decline of British hegemony and American hegemony did not lead to military conflict between Washington and London, though it did take place in the broader context of two world wars.

[3] AFK Organski, World politics (New York 1958), p. 19

[4] Robert Gilpin, War and change in world politics (Cambridge 1981); Paul Kennedy, The rise and fall of the great powers (New York 1987)

[5] Congressional Budget Office, The 2022 long-term budget outlook, 2022

[6] John Mearsheimer, The tragedy of great power politics (New York 2001)

[7] Joshua Itkowitz Shifrinson, Strategy on the upward slope, The Oxford Handbook of Grand Strategy, 2017

[8] Kenneth Waltz, The stability of the bipolar world, Daedalus, 93(3), 1964; John Mearsheimer, The tragedy of great power politics (New York 2001)

[9] Paul MacDonald and Joseph Parent, Grand strategies of declining powers, The Oxford Handbook of Grand Strategy, 2017

[10] MacDonald and Parent (2018) find that this is the most frequently adopted strategy, even though it translates into mixed outcomes from the declining state’s perspective.

[11] White House, National Security Strategy, 2022

[12] For example, Mark Brawley, Afterglow or adjustment? Domestic institutions and responses to overstretch (New York 1999)